I found an interesting case involving nullable reference types, the highlight feature of C# 8.

The Problem

CONTEXT For this post, we’re going to assume that nullable reference types is enabled.

Let’s say that I give you a variable, list, and tell you it’s of type List<string>. So the list is not null, and the items in it are not null. So this:

var first = list.FirstOrDefault();

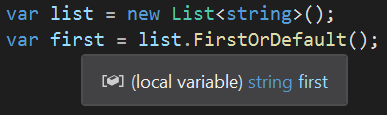

would assign a definitely non-null string, right? Visual Studio’s analyzer says first is non-null:

So it must have a value, right?

But in the screenshot above, list is empty. So what value is in the non-nullable string variable first?

Before we can answer that, we need to look at what “nullable reference types” really means.

Under the covers

Nullable reference types are really just a compiler trick over some interesting attributes. (Hmm… sounds familiar.) There’s nothing that actually states that such a variable can’t be null; just that it’s not intended to be null.

Contrast this to nullable value types, like int?. This syntax is just a shorthand for an int wrapped in a Nullable<T>, or Nullable<int>. Note that this is a completely different type. If you try to assign an int? to an int, you’ll get a compiler error. (Nullable<T> defines an implicit conversion so that the assignment works the other way.)

But for our case, the CLR type is still simply System.String, which is most definitely nullable.

Having a think

So what this means is even with nullable references turned on, a string variable is exactly the same as a string? variable at runtime. It can be null, and if you don’t check it, you might wish you had.

So why doesn’t the analysis engine work for .FirstOrDefault()? Let’s have a look at the signature.

public static void T FirstOrDefault<T>(this IEnumerable<T> collection) { ... }

It seems like the solution is to make the return type T?. That should fix the problem, right? Well, no. Suppose T is int or some other value type. If that’s the case, then it’s saying the method returns Nullable<T>, which, as stated before, is a different type. In fact the compiler yells at you saying you can’t put the nullability operator ? on a generic type without first constraining that type with either class or struct for this very reason.

But we can’t add a type constraint because we want this method to work with both reference and value types, and the compiler won’t let us add both constraints. (What’s the sense of that anyway?)

Maybe we could create overloads, one for reference types and one for value types? No, when you try that, the compiler yells at you for creating two methods with the same signature, even though they have disparate type constraints, meaning they could be differentiated from one another when called.

Seems like we’re stuck with dealing with the fact that first just might be null, regardless of what the compiler says.

So what’s the benefit of nullable reference types?

A couple months ago, I went through the exercise of updating Manatee.Json to use nullable reference types, just to see if it finds anything. It did. I fixed a few bugs and identified some other weaknesses because of the effort. As I mentioned in my previous post, Jon Skeet had a similar experience when updating NodaTime.

However, this is an edge case that just can’t be resolved by the compiler with nullable reference analysis in its current state. One thing about tools, however, is that they continue to improve. So maybe a future iteration of the analysis engine will be able to solve this.

A workaround

The root of the problem is that .FirstOrDefault<T>() returns a T. So to solve this, we just need to explicitly specify T to be nullable, i.e. string?. Now it will tell the compiler that what it returns is intended to be potentially null.

var first = list.FirstOrDefault<string?>();

Of coursse, Visual Studio will dim the <string?> part and the compiler will tell you it’s not necessary because that portion of the analysis engine considers string and string? to be the same type, as it should (otherwise you’d get an assignment error).

So pick your poison. Personally, I’m of two opinions.

On one hand, your code shouldn’t have to work around the tool. The tool is giving you bad information by saying first isn’t nullable. The tool should be fixed.

But on the other hand, I think knowing whether something could be null is pretty important.

NOTE By the way, Resharper comes to the same conclusion as the compiler.